Today, I—Mattia Puppo, VC analyst at NextSTEP—along with Henri Ngo, VC investor at Galion.exe—will delve into the fascinating world of physics, seeking to uncover its correlations and potential applications in the Venture Capital industry. We will also try to uncover the truth behind one of this industry's most critical questions: “Will there ever be enough startups?” Stay with us until the end to find out the answer.

Introduction

For most of us, physics is the mathematical and conceptual framework that explains the world around us. Surprisingly, its principles can also be applied to the VC Landscape.

Unlike private equity and late-stage VC, early-stage investing is often more an art than a science. Without concrete data to guide decision-making, investors must rely on intuition, patterns, and broader frameworks to build conviction.

As English researcher Paul Wilmott stated, just after the 2007 stock market collapse in its Quant Manifesto “Physics, because of its astonishing success at predicting the future behavior of material objects from their present state, has inspired most financial modeling”. However, financial models often fall short not because they are wrong but because they are built on assumptions and parameters that may not hold in our world. If modeling financial markets is already a challenge, how can we expect to apply such frameworks to the even more unpredictable world of Venture Capital?

Today, rather than directly applying financial modeling to VC, we will explore two fundamental physics concepts–power laws and entropy–that strongly correlate with the dynamics of venture investing. Physics provides well-tested frameworks to model uncertainty, risk, and nonlinear behavior, offering deeper insights beyond traditional financial models.

Recognizing that natural laws govern both the physical and business worlds can help us better understand how VC funds and startups operate.

Let’s dive in.

VC’s power law: small bets, massive payoffs

The “Homerun” that returns the fund

Just as energy isn’t distributed equally across a system, returns in venture capital don’t follow a normal distribution; they follow extreme, exponential trajectories. The dynamics of startup success and investment returns mirror power laws, inertia, and even thermodynamics.

As we said, venture capital returns are not normally distributed; they follow a power law distribution.

What this means essentially is that a small number of investments generate the majority of returns, while the remaining majority of investments yield modest or negative outcomes.

In this sense VC outcomes are “highly skewed” – a few big winners account for nearly all the gains.

This pattern has been observed in large-scale data. For example, an analysis of 21,640 U.S. venture financings between 2004 and 2013 confirmed that ~65% of VC investments lose money, ~25% produce only modest 1–5× returns, and only ~10% return more than 5×. The extreme tail is very thin: only about 0.4% of deals achieved a 50× or greater “grand slam” outcome, which is where VC thrives, this is why the performance of venture portfolios is dominated by a tiny fraction of outliers.

Babe Ruth effect

Outliers, as we pointed out, are very important for VCs who are subject to the Babe Ruth effect, a phenomenon named after American baseball player Babe Ruth who even if he had a high number of strikeouts is remembered as a superstar player for hitting many home runs.

VCs need exactly that, those home runs and outliers that alone can pay back the entire fund; home runs are what VCs are constantly on the hunt for considering their need to offset the many losses and small wins they register. That’s why VCs focus on funding startups with vast market potential and high growth prospects. If a VC decides not to invest in your startup, it doesn’t necessarily mean your idea is flawed–it’s often a matter of alignment. VCs are constantly searching for the next Uber or Airbnb, a breakthrough success that fits their investment strategy.

Many times, though, it is difficult even for a home run to have a big impact on the fund, for example, a single $10M ticket needs to return ~12.5× just to pay back a fund of $125M before considering profits. For this reason, VC funds prefer to invest in a diverse portfolio of startups, increasing their chances of backing a breakout success—often following the "spray and pray" philosophy.

Additionally, the earlier a fund invests, the more concentrated its results tend to be. In 2012, Y Combinator disclosed that three-quarters of its portfolio gains came from just 2 out of 280 investments–a clear demonstration of the power law in action.

From disorder to disruption: the thermodynamics of startups

The 2nd law of thermodynamics

This principle explains why natural processes tend to move toward greater disorder rather than order. A common physics example is a hot cup of coffee placed in a cooler room—heat flows from the coffee to the surrounding air, increasing the randomness of molecular motion and the overall entropy of the system. Over time, the coffee inevitably cools down as energy disperses and becomes more evenly distributed.

The same principle applies to all systems: disorder naturally increases unless energy is continuously applied to maintain order. As Stephen Hawking put it, “Disorder, or entropy, always increases with time… things always tend to go wrong.'"

Maintaining order to survive

Maintaining order in a system requires a continuous input of effort and energy; without it, all systems naturally drift toward disorder. This principle of entropy in physics also applies to venture capital, startups, and the innovation landscape, where sustained effort is essential to prevent stagnation or decline. Just as physical systems require energy to resist entropy, mature businesses must constantly adapt, iterate, and innovate to navigate market shifts, outpace competition, and sustain long-term growth. What’s interesting is what happens when mature businesses, such as corporations, lose the ability to combat entropy—this is where startups can find hidden doors of success.

Markets and industries that startups aim to disrupt naturally move toward higher entropy, increasing in complexity and disorder over time. For example, when new technologies emerge, they lower barriers to entry, allowing more competitors to enter the space. This rise in competition leads to the development of diverse solutions, making the market more fragmented and dynamic.

Regulatory factors also play a significant role as consumer behaviors evolve and industries undergo transformation. This continuous increase in entropy is important on two sides, first of all it creates opportunities for startups to rise and thrive. They can identify inefficiencies, streamline processes, and introduce disruptive innovations. Startups can capitalize on the disorder that unsettles traditional markets. While this dynamic opens doors for agile and adaptive innovators, it simultaneously poses a significant challenge for established corporations. Companies that fail to keep pace with change—such as BlackBerry and Nokia—struggle to maintain their competitive edge, often losing relevance as more innovative players reshape the landscape.

Accelerating entropy

This theory has been perfectly outlined by Packy McCormick who states that “every industry is on a journey of increasing, accelerating entropy. More choice, speed, and flexibility create more chaos, which in turn creates opportunities for companies to capture value by temporarily bringing order to the ever-increasing entropy.”

If you went so far, you can confidently reply to the question “Will there ever be enough startups?” The conclusion is that no, there will never be “enough startups” because of this exact reason, the market is not a static system, it’s dynamic. This ever-expanding chaos opens continual opportunities for innovation. Successful startups aiming to seize traction by offering solutions that solve inefficiencies can be viewed as “entropy wranglers”, they find ways to impose new order on a chaotic market. Industry evolution is driven by this cyclical battle between entropy and order and it will never stop.

In the realm of Industry evolution, economist Schumpeter introduced the concept of creative destruction stating that industries are built when entrepreneurs find ways to use creativity to develop new solutions that disrupt pre-existing alternatives creating pockets of order (competitive advantages) in an industry that needs a constant input of energy, in the form of capital, work and innovation to create order with creativity.

Other interpretations of entropy are manifested in the internal complexity and organizational chaos startups face when growing. Every startup starts simple but as it scales up, adding new layers of employees, products, and processes it risks entropic drift the same way the outlying industry does. This is where growing scale-ups must input their focus and energy to avoid entropy drift and cultural decay. This is something Amazon is very good at doing, it now has an incredibly complex structure but still manages to remain flexible and agile, well managing the risk of increasing disorder.

Personal entropy

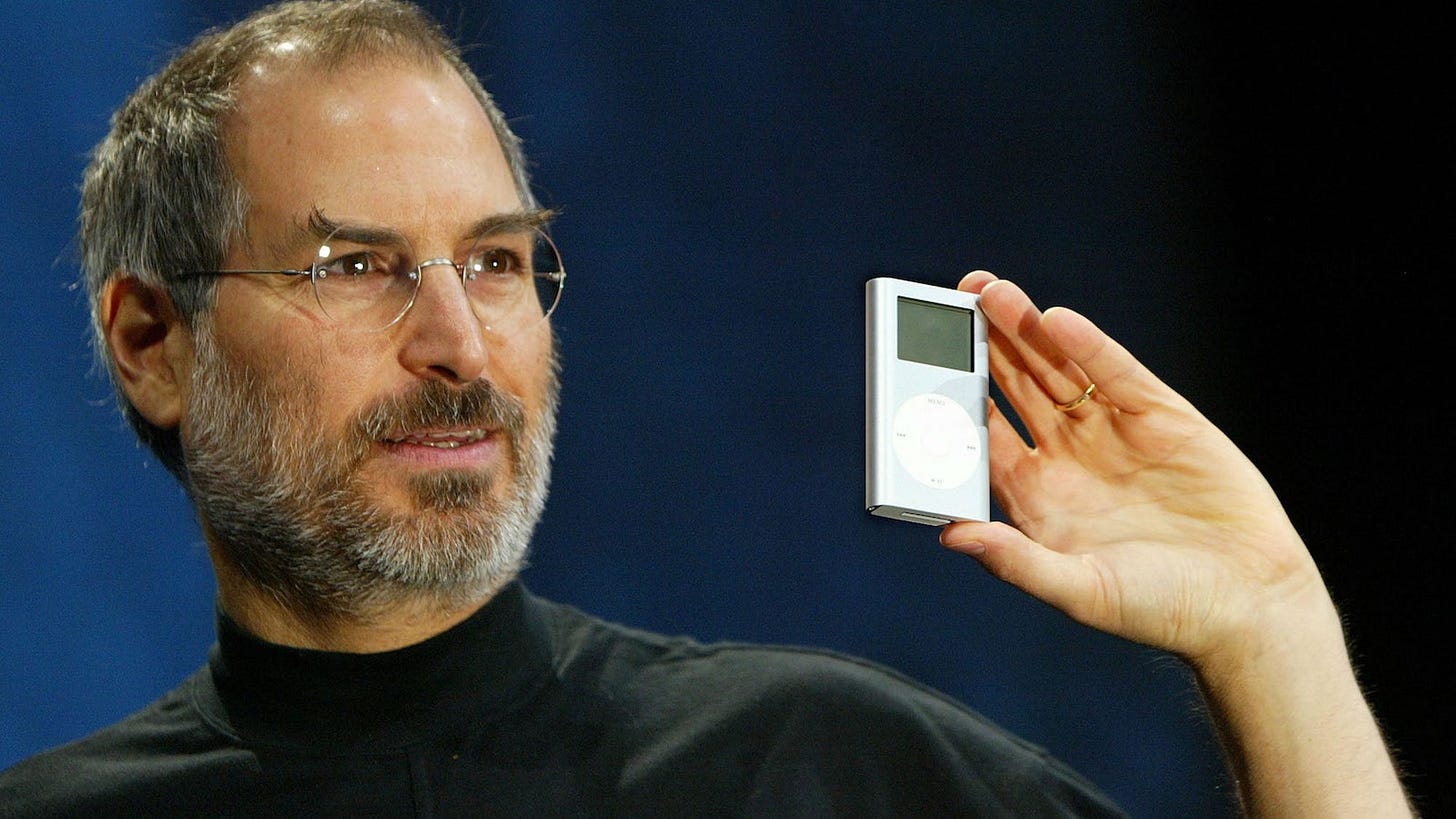

Let’s not forget that before anything else, startups are just a group of people building something users care about, and personal entropy plays just as important a role as the entropy within a startup itself. For this reason, after discussing entropy within companies we want to introduce a humorous anecdote on personal entropy minimization and that is Steve Jobs’s black turtleneck. This is a popular example of extreme simplification aimed at minimizing personal entropy, it is a way to eliminate trivial decisions and maintain focus.

Jobs reportedly owned hundreds of them, wearing them daily as part of his minimalist uniform, effectively reducing cognitive entropy and mental disorder from excessive choices, an extreme example of streamlining even the easiest decision-making processes to minimize informational and psychological entropy.

Entropy in the VC ecosystem

Startups are not the only system subject to entropy, the VC ecosystem as well has experienced an “entropy jump” in recent years exploding in complexity and especially scale.

In the past, a handful of firms on Sand Hill Road controlled most of the venture capital. However, we have since witnessed a commoditization of capital, driven in part by its abundance and global distribution. This shift became especially evident in 2021 when VC investments totaled $330 billion—double the previous record set just a year earlier.

The shift from a lower-entropy state in the VC ecosystem to a much higher entropy state has been caused not only by this growth in the influx of money but also by a surge in the number of players, not only did mega funds grow larger but dozens of new micro-VCs, solo angel investors and crowdfunding platforms appeared, widening the solutions that startups can adopt to finance their initial growth and increasing the entropy of the financing environment.

In the future, we might see a slowdown in the VC ecosystem due to higher interest rates since 2022-2023 which may cool down the funding environment and consolidate it with disorder (expressed in excess startups/funds) exiting the market and bringing new structure to this complex system.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the interplay of power laws and entropy reveals that the venture capital landscape mirrors the natural order of the physical world—a realm where chaos fuels opportunity and only a handful of breakthrough innovations propel the entire system forward. Just as energy disperses and order requires constant input to sustain itself, the startup ecosystem continuously evolves, creating fresh challenges and untapped markets for startups to exploit. There will never be “enough startups” because the inherent disorder of our dynamic world always leaves space for new ideas, inventive minds, and the relentless drive to impose order on chaos.